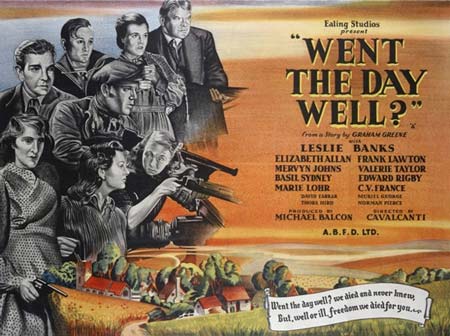

…blinds a Nazi invader with pepper, then splits his skull with the kindling hatchet in WENT THE DAY WELL? (1942). She’s Mrs Collins, postmistress at the idyllic village of Bramley End; he’s one of a German unit who have infiltrated the place during the Whitsun weekend (May 23rd – 25th) of 1942. They’re in British uniforms and all speak & understand English … save one. If that situation rings a bell then you’re probably thinking of Jack Higgins’ THE EAGLE HAS LANDED filmed 36 years later. Graham Greene wrote the story for this one, it was produced by Michael Balcon and artfully directed at a gallop by Cavalcanti. Music by William Walton.

I discovered this movie about 20 years ago and was amazed by the atmosphere, the extreme violence, the pace and the infinite subtleties of the propaganda. The film in told in flashback. A framing talk to camera by Mervyn Johns, showing us German graves in a rural churchyard – “they wanted a bit of England and this is all they got”, emphasises that we are looking back at trauma from a position of security “after the war was over and old Hitler got what was coming to him”; after a living nightmare broke out in a toy village which learned to grow fangs and claws. Thus reassured – for when WENT THE DAY WELL? was first released in 1942 the outcome of WW2 was very far from certain – contemporary British audiences were taught a number of salutary lessons. Recently this film has much revived and discussed, the consensus being that it was designed essentially as a morale-boosting exercise showing all sections of society (in a time still obsessed by class) seamlessly bonding to defeat the invader. I see something very different.

For WENT THE DAY WELL? seems to have been intended – under a thin veneer of roses round the door cosiness, and even comic touches – to frighten the life out of everyone who saw it. Imminent danger of invasion had passed in 1942 but was by no means gone, and it is never explained how the outfit of 60 Germans have penetrated Middle England: “the forces of evil” have come like a thief in the night or like Dracula, manifesting in a mist. A terrifying almost uncanny mystery in brilliant summer sunshine: all we know is, that they are here – now.

The film is a brilliantly paced series of show ‘n’ tell lessons as clear as a medieval morality play. It can be highly subversive in its attitudes: roses have thorns; the sacred hospitality extended to strangers is unwise and likely to be abused; trust animal instinct and intuition, not common sense; don’t be afraid of making a fool of yourself. Take Mrs Collins and that axe. By killing the invader she is atoning for her slackness and want of vigilance earlier in the picture: losing telegrams, ignoring her feelings that something’s strangely amiss. However, as her billet lies dead in the wreckage of the tea table (like all Nazis he’s been filling his greedy face at someone else’s expense*) the camera zooms in on his fallen revolver. The heroic but disorganised postmistress (ultimately responsible for all national communications) foolishly fails to retrieve the vital gun for future use. So that, although she tries to phone for help, she is consequently defenceless when the fallen man’s comrade bursts in and then and there atrociously bayonets “the old woman” to death +.

Nearly all the villagers who are seen being wilfully careless, lazy – (“it’s probably a Czech or a Pole…We’ll let sleeping dogs lie..”) – or heedless of official home front procedure are killed off by the scriptwriters. The deaths of these defaulters are given a final heroic gloss in this expert piece of public information – they are after all British, and native casualness beats heartless totalitarian efficiency hands down – but nonetheless it is made clear why they have to die. The Home Guard are wiped out because they ignore the tolling of the church bell** – “… couldn’t have. That’s the signal enemy parachutists have landed”. The village policeman*** fails to check the invaders’ credentials upon arrival – he’s more concerned with the pointless etiquette of being surprised while shaving – and is subsequently and aptly stabbed in the back by the quisling, Oliver Wilsford (Leslie Banks). The lady of the manor though full of politically correct platitudes (“you mustn’t waste food in wartime”) loftily brushes aside everyone’s all-too-well-founded fears – “it’s all right, don’t worry, it’s all right”# – and is blown to bits by a hand grenade; although she’s allowed to meet her end in an act of self-sacrifice which saves the local children. What’s more she’s played by national treasure Marie Lohr: all the faces (English AND German characters) in this film are carefully chosen as well-known & loved by contemporary British audiences, as though to ram home the message that this horror could happen to us all. ANYONE might turn out to be a Fifth Columnist or his victim. Familiar and beloved does not necessarily mean trustworthy.

The children, however, the future of postwar Britain, are all calm, resourceful and alert: “you ought not to tell!” Young George¤, the cheeky Cockney evacuee who eventually raises the alarm and calls in the British troops, despite being shot in the leg, is one of the few unqualified heroes of the picture. There’s a sharp point here, too: it’s a village outsider – ” we always call them foreigners round this way” – who brings about the downfall of the true aliens, the Nazis++. It’s also George who is posed the question “Do you know what morale is?” The succinct answer is so outrageously racist by today’s standards that I dare not repeat it here. It’s still to be found on film, though – for now.

The other unblemished hero of the piece is Nora (Valerie Taylor)¤¤, the vicar’s middle-aged spinster daughter – “my dear! Another cup!” – who we see from her first appearance is practical and patriotic: “a very good citizen”. She has instructions for dealing with a gas attack pasted up in the hall cupboard and thinks that as the French “let us down so abominably …they deserve to suffer for it”. It is Nora and George, already suspicious, who make the key discovery that the German commandant billeted at the vicarage sleeps in “posh pyjamas” and what’s more ( stupidly and gluttonously – as you’d expect from a Nazi) he keeps Viennese chocolate in his kit bag. Now, Nora has a crush on the traitor Wilsford who to the viewer has all the marks of a degenerate about him: florid ties, flowery scarves and an oily manner. Bloomsbury-style frescoes adorn the walls of his cottage. Initially beguiled by these arty affectations, Nora nonetheless sets aside her affections, formulates her suspicions and ultimately shoots Wilsford dead in a quite extraordinary sequence of such verisimilitude that I wonder whether Valerie Taylor was not given a real gun on set and let rip, kickback and all. “Each man kills the thing he loves”…

Thora Hird also keeps a level head as the sharp-shooting land girl Ivy (“I once won a bottle of scent at Blackpool”): here expectations are again reversed, for the character is trailed as a man-mad featherhead but Northern nous comes to the fore and in the final shoot-out Ivy has a go as a cool-headed killer. Her house mate is played by Elizabeth Allan whose dad was golf partner to Lemon Wedge’s grandfather. Miss Allan was said to have been an intimate of Dietrich so there’s a cute (and faintly risque) in-joke as she and Thora attempt to smuggle out messages pencilled on eggshells under the nose of their guard – “Go on, Marlene, do your stuff!”¥

So, what do we smell in this curiously compelling film? The stink of treachery that’s for sure; the smell of “the lowest of the low”¥¥ and the corruption which breeds the reek of blood, cold steel and bashed-in heads. But more movingly, there’s the magical pervasive fragrance of an idyllic English early summer, all the more beautiful for being in danger of being lost for ever under the heel of the invader. Despite, or maybe because of the black and white stock, evoking an instant nostalgia even in 1942, “the darling buds of May” were never more profuse nor so heavily scented. The exteriors were shot on location in the impossibly olde worlde village of Turville in Buckinghamshire. The camera dazzles the eye with leafy lanes, carefree cyclists, cornfields, windmills, flocks of sheep, dream cottages and church towers while nesting birds sing like mad on the soundtrack. The delicious aromas of freshly baked bread, roasting Sunday joints, plum tart, apples and cider fill the village kitchens: the smells of England, home and beauty. Jars of wild & garden flowers decorate every studio interior. Oliver Wilsford offers Nora a rose from a vase: the traitor’s symbolic snitching of England’s national flower. The climactic battle for Bramley End takes place in the exquisite water gardens of the Georgian manor house. As the marauders are gunned down amid the ponds and lilies we recognise another neat bit of dramatic foreshadowing: Hitler’s crossing of the Channel waters will end, we are told, equally disastrously. Smoke from the smashed-up manor rises with that of shells, rifles and grenades but also from priceless antiques piled up as barricades: the land girls throw a great clock – “grandfather!” – on top. Now is the hour of youth & renewal. A new downsized Britain will rise from the ashes: full of vigour, ruthlessness and raw courage to atone for the stale smug appeasement complacency of the old generation. The house’s mistress lies gloriously dead within her home, like a Valkyrie on her funeral pyre. Ambiguous ironies to the last!

“Went the day well? We died and never knew,

But, well or ill, freedom we died for you.”

* “I don’t know when they’re more unpleasant: when they’re dead or when they’re guzzling our rations” . Nazis also boast a Fascist disregard for decent conventions: “I am not married but I have 2 fine sons who will soon be old enough to fight”.

+ Her dopey assistant Daisy – the village Holy Fool, played by future TV comic heroine Patricia Hayes – is smashed in the face by a Nazi: “Obey orders in future”. The shock of all this brutality is compounded by it’s being so totally unexpected in a British picture of this era. This is how everyday life will be, post-Invasion!

** there’s also a hint that the Home Guard are over-prodigal in food consumption – too many packed sandwiches for lunch. Later on, references to the Siege of Paris in 1871 remind audiences with grim facetiousness of the extreme straits of wartime starvation – “Rats were quite a delicacy apparently. I wonder which is the best end of neck of giraffe… “. Meanwhile drunken Nazi sadist David Farrar messily wolfs down an eclair.

*** Johnny Schofield: indispensable and adorable character actor of the period. Expert in under-playing soldiers, batmen, barmen, coppers, next-door- neighbours, landlords and waiters.

# and this after the vicar is gunned down in his own church.

¤ Harry Fowler: as an adult he has a moment in THE NANNY as the angry milkman seen off by Bette Davis (1965).

++ could George (the King’s name of course – and Washington’s) be an extended metaphor for the arrival of the USA on the side of the Allies? And an embodiment of the spirit of Blitzed London?

¤¤ better known for her stage work. Her final film role was as Mme Denise in Polanski’s REPULSION (1965).

¥ German-born Marlene Dietrich renounced her nationality in protest against Nazism, was proscribed by Hitler and fought gallantly on the side of the Allies.

¥¥ Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother’s laconic definition of a traitor.